New Antibiotics: Keeping Ahead of Resistant Bacteria

Antibiotics – medicaments against harmful bacteria – are among the greatest achievements of medicine. It is thanks to them that lung infections, wound infections, scarlet fever, syphilis and many other diseases have lost their terror. Thus, today in Germany, bacterial infections rank far behind cardiovascular diseases and cancer as causes of death.

Antibiotics classes with year of introduction

Download the chart "Antibiotika-Klassen weltweit" as PDF (in German)

Antibiotics effective against more than 80 different kinds of bacteria have already been developed. They belong to various classes (see chart), each of which is characterized by a different basic molecular structure and mode of action. The majority of new classes were introduced between the 1940s and 1960s; but six new classes have also been introduced since the start of the present century.

In the 1980s and 1990s

The majority of market launches took place, not between 1940 and 1969 but between 1980 and 1999. In that period, in particular the classes of macrolides, cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones were expanded (see bar graph). Through changes in their molecular structure it was possible to improve the active ingredients so that, for example, they were effective against even more types of bacteria or were better able to reach the affected tissue.

Gram-Negative Bacteria

Only colored bacteria show up in an optical microscope. With a method discovered by Christian Gram (1884), many kinds of bacteria can be colored dark violet; but other kinds can only be colored a weak pink. Because these types take the gram coloration so poorly, they are called gram-negative. Their cell wall is different from other bacteria. This not only makes them difficult to color, it also protects them from many antibiotics. In recent years, some of these have increasingly developed multi-resistances.

Even today, the majority of bacterial infections can still be well treated with the substances from the 20th century. But increasingly, patients and physicians are also confronted by bacteria that have developed powers of resistance against one or more of these antibiotics. Physicians must then switch to a different antibiotic. The multi-resistant "hospital germ" MRSA has achieved notoriety, as has multi-resistant tuberculosis. There are also increasing reports of infections with so-called multi-resistant gram-negatives (a type of bacteria against which in any case only some of the older antibiotics are effective). These include for example the Neisseria bacteria which cause gonorrhea (tripper). An overview of the resistance situation in Germany is provided by the report GERMAP 2015 by the Paul Ehrlich Society for Chemotherapy and the Division of Infectious Diseases of the University Hospital Freiburg.

Therefore, almost all of the eight antibiotics that came out between 2001 and 2010 were explicitly developed with the goal of overcoming one or more existing resistances.

New Introductions Since 2011

The antibiotics that have been launched on the market in the present decade have also been explicitly developed to combat problem bacteria – either resistant forms of "common" bacteria, or bacteria that have previously never been successfully combated:

- 2012: The broad-spectrum antibiotic ceftaroline (a cephalosporin antibiotic), effective against the multi-resistant hospital germ MRSA among other things.

- 2013: The antibiotic fidaxomicin against the intestinal Clostridium difficile bacterium, which causes severe intestinal colic.

- 2014: Bedaquiline and delamanid against tuberculosis (the first new substances since 1995) in combination with older drugs to combat multi-resistant bacteria. There was also the older TB ingredient para-aminosalicylic acid in a new and easier form of administration (granulate). More about this here. Also the antibiotic telavancin, specifically against MRSA from lung infections acquired in hospital (withdrawn from the market in 2018 due to too low sales), as well as the antibiotic ceftobiprole (a cephalosporin antibiotic) which can be used against lung infections from gram-positive bacteria (also MRSA) as well as from non-multi-resistant gram-negative bacteria.

- 2015: The antibiotic tedizolid (an oxazolidinone), against complicated skin and soft tissue infections with gram-positive bacteria, also MRSA.

Combination drug ceftolozane + tazobactam (a new cephalosporin + an approved beta-lactamase inhibitor) against complicated abdominal and urinary tract infections with certain multi-resistant gram-negative bacteria. - 2016: antibiotic oritavancin (a lipoglycopeptide) against skin and soft tissue infections with gram-positive bacteria, also MRSA.

antibiotic dalbavancin (a lipoglycopeptide) against complicated skin infections with gram-positive bacteria, also MRSA. - 2017: The antibiotic ceftazidime + avibactam (a cephalosporin + new beta-lactamase inhibitor) against respiratory tract, urinary tract and abdominal infections with gram-negative bacteria (including those with certain beta-lactamase resistances or with Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase) incl. Pseudomonas.

- 2018: The antibiotic eravacycline (a fluorocycline) against complicated abdominal infections has been approved but is not yet on the market. Bezlotoxumab, a monoclonal antibody, was also launched which can also be applied in addition to an antibiotic against the intestinal bacterium Clostridium difficile; it neutralizes the toxin excreted from C. difficile.

Coming Antibiotics

Approval procedures are currently running in the EU for two non-pathogen-specific antibiotics, and further such antibiotics are in the final phase of clinical testing, so-called Phase III (see table). There are also antibiotics and other antibacterial substances specifically against individual problem bacteria. Further antibiotics are currently in the early stages of clinical and preclinical development.

Non-pathogen-specific antibiotics in Phase III development, in approval procedures or before market launch. (Status as at 02.10.2018; excluding drugs specifically targeted against one form of bacteria)

| Active ingredient of the new antibiotic (class) | Status in the EU | Fields of application |

| Meropenem + vaborbactam (RPX-7009) (a carbapenem + new beta-lactamase inhibitor) | In EU approval procedure, approval recommended in September 2018(1) | Infections with gram-negative bacteria, including Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteria |

| Delafloxacin (a fluoroquinolone) | In EU approval procedure(2) | Skin, lung, abdominal and urinary tract infections with gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria; also MRSA infections |

| Nemonoxacin (a non-fluorine quinolone) | Phase III (already approved in China and Taiwan) | Lung infections; complicated skin and soft tissue infections, also from MRSA |

| Plazomicin (an aminoglycoside) | Phase III(3) | Sepsis, urinary tract infections, among others with multi-resistant gram-negative enterobacteria (also with carbapenem resistance) |

| Zabofloxacin (a fluoroquinolone) | Phase III | Lung infections with gram-positive bacteria |

| Omadacycline (an amino-mythylcycline and tetracycline analog) | Phase III(4) | Skin infections and lung infections, urinary tract and abdominal infections with gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria |

| Cefilavancin (a telavancin heterodimer) | Phase III | Infections with gram-positive bacteria, also from MRSA |

| Lefamulin (a pleuromutilin for oral and i.v. application) | Phase III | Lung infections, skin infections (also with potential against multi-resistant gram-negative bacteria, including gonorrhea pathogens) |

| Iclaprim (an inhibitor of bacterial dihydrofolate reductase) | Phase III(5) | Skin infections with gram-positive bacteria, also MRSA |

| Cefiderocol (S-649266, a cephem antibiotic) | Phase III | Infections with multi-resistant gram-negative bacteria |

| Lascufloxacin (a fluoroquinolone) | Phase III | Infections with gram-positive bacteria, also from MRSA |

| Imipenem + cilastatin + relebactam (known carbapenem antibiotic, known booster for imipenem, new inhibitor of beta-lactamase types A and C) | Phase III | Pneumonias and other infections with gram-negative bacteria |

| MRX-I (an oxazolidinone antibiotic) | Phase III | Infections with gram-positive bacteria including MRSA and Vancomycin-Resistant Enterococci (VRE) |

| Solithromycin (a ketolide) | Phase III (6) | Respiratory tract infections; also against skin, abdominal and urinary tract infections incl. gonorrhea as well as H. pylori infections in clinical trial |

| Sulopenem (a carbapenem) | Phase III (7) | Complex urinary tract infections, also through multi-resistant gram-negative bacteria |

Source: vfa, PharmaProjects, press releases, EMA, clinicaltrials.gov

Anticipated antibiotics and other anti-infectives in development, targeted against specific bacteria, that have at least reached Phase III (status as at 04.06.2018)

| Active ingredient of the new antibiotic (class) | Status in the EU | Fields of application |

| SQ-109 (an ethambutol analog) | Phase III | Multi-resistant tuberculosis |

| Pretomanid (in combination with moxifloxacin and pyrazinamide) | Phase III(8) | Multi-resistant tuberculosis |

| Murepavadin (a cyclic peptide) | Phase III | Treatment of infections with Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| Anti-Pseudomonas IgY (a monoclonal antibody) | Phase III | Prevention of infections with Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| Anthrax-Immunglobulin (polyclonal serum) | Phase III(9) | Treatment of anthrax infections |

| Obiltoxaximab (a monoclonal antibody) | Phase III(10) | Antitoxin against anthrax |

| Sarecycline (a narrow-spectrum tetracycline) | Phase III(11) | Treatment of acne and facial erysipelas |

| Zoliflodacin (a topoisomerase inhibitor antibiotic) | Phase III(12) | Uncomplicated gonorrhea |

Source: vfa, PharmaProjects, company press releases, GARDP

In addition there are also new inhalable antibiotics based on proven active ingredients for use against lung infections.

Antibiotics Research and Development in Companies

A range of large companies and more that 50 small and medium-sized companies worldwide are currently working on new antibiotics and other antibacterial drugs.

Pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies developing new antibiotics and other antibacterial drugs (excluding firms only developing TB medicaments; status as at 17.08.2018)

| Large Companies: | Small and Medium-Sized Companies: |

| AstraZeneca (UK)(13) , GSK (UK, laboratories in USA), Janssen (Actelion, USA), MSD (USA), Pfizer (USA)(14) , Roche (CH), Sanofi (F, laboratories in D and F) | Achaogen (USA), AiCuris (D), Allecra Therapeutics (D), Basilea Pharmaceutica (CH), BC World (S. Korea), Boston Pharmaceuticals (USA), Cardeas Pharma(14) (USA), cellceutix (USA), Cempra (USA), Cosmo Pharmaceuticals (I), CrystalGenomics (S. Korea), CURx Pharmaceuticals (USA)(14) , Cyclenium (Canada), Debiopharm (CH), Destiny Pharma (UK), Discuva (UK), Dong-A (S. Korea), Dream Pharma (S. Korea), Durata Therapeutics (USA), Elorac (USA), Enanta (USA), EnBiotix (USA), Entasis (USA), Evotec (D), Infectex (Russland), Kyorin (JP), Lee's Pharmaceutical(14) (Hong Kong), LegoChem Biosciences (S. Korea), Lisando (Liechtenstein, laboratories in D), Lytix Biopharma (N), Kyorin (JP), Macrolide (USA), Melinta (USA), MerLion Pharmaceuticals (Singapore), MicuRx Pharmaceuticals (USA and China), Nabriva (AU), Naicons (I), Nanotherapeutics (USA)(14) , NovaBay Pharmaceuticals (USA), Orchid Pharmaceuticals (India), Paratek Pharmaceuticals (USA), Polyphor (CH), RedHill Biopharma (Israel)(14) , Sequella (USA), Shionogi (JP), Sihuan Pharm (China), Summit (UK), Tetraphase Pharmaceuticals (USA), The Medicines Company (USA), Theravance Biopharma (USA), Wockhardt (India and USA), Zavante Therapeutics (USA), and others. |

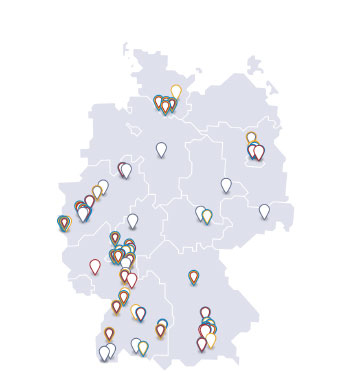

The majority of these companies operate their laboratories in the USA, but also in Germany, Austria and Switzerland, both industrial and academic pharmaceutical researchers are working on new substances. This is shown in the following map.

Antibiotics research and development in Germany, Austria and Switzerland

Two reports from January 2018 show the status of the activities of pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies with regard to new antibacterial drugs:

- The Progress Report of the AMR Industry Alliance (see below for further information).

- The report"Antimicrobial Resistance Benchmark 2018" by the Access to Medicine Foundation. In this, however, only 30 selected pharmaceutical companies were studied and numerous smaller companies like AiCuris and Evotec in Germany or Basilea Pharmaceutica in Switzerland were disregarded. Thus the report inevitably remains incomplete. Large parts of the report are also concerned with non-bacterial diseases such as hepatitis B, AIDS or malaria.

Efforts for the Expansion of Antibiotics Research

Despite these successes, there is a great need for further antibiotics because the resistance situation is expected to become more acute. In particular, the search is on for innovative substances against gram-negative bacteria as well as against infections that have always been difficult to treat such as pseudomonas infection of the lungs, Buruli ulcers and infections in dead tissue. However, it has proved to be extremely difficult to discover further antibiotics classes with a new mode of action. And the earnings potential of such products is generally very low, because as reserve antibiotics they are deployed as rarely as possible. Thus it can be assumed that such new antibiotics cannot be refinanced from their own earnings alone, and the researching companies are therefore dependent on partners who can share the economic burdens and risks.

Despite these successes, there is a great need for further antibiotics because the resistance situation is expected to become more acute. In particular, the search is on for innovative substances against gram-negative bacteria as well as against infections that have always been difficult to treat such as pseudomonas infection of the lungs, Buruli ulcers and infections in dead tissue. However, it has proved to be extremely difficult to discover further antibiotics classes with a new mode of action. And the earnings potential of such products is generally very low, because as reserve antibiotics they are deployed as rarely as possible. Thus it can be assumed that such new antibiotics cannot be refinanced from their own earnings alone, and the researching companies are therefore dependent on partners who can share the economic burdens and risks.

The EU Commission's "Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance" from 2011 (which was followed in 2017 by the "Action Plan against Antimicrobial Resistance", see below) offered the first paths to a solution, which included the research program NewDrugs4BadBugs (ND4BB) in the framework of the Product Development Partnership (PDP) Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI). Within this program, which was launched in 2012 for a period of seven years, academic research groups and companies could jointly spend 223.7 million EUR for this purpose. Numerous pharmaceutical companies took part. IMI is a Public-Private Partnership of the European Commission and the researching pharmaceutical industry in Europe.

Among other things, ND4BB focuses primarily on further development of the design of clinical antibiotics studies, and organizes a comprehensive exchange of information (especially about failed projects) among the participating academic and industrial partners in order to increase the chances for the development of new antibiotics. Particular emphasis is placed here on the discovery of new substances specifically against gram-negative bacteria.

Another cooperation was launched in 2016 by the World Health Organization WHO together with the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDi): GARDP, the Global Antibiotic Research & Development Partnership. DNDi is an organization for Product Development Partnerships, principally specializing in the development of new drugs against neglected tropical diseases together with companies and academic research institutions. The new organization also works in a similar way to DNDi. It concentrates on those projects that, on account of their lack of economic viability, cannot be undertaken or brought to a conclusion by companies acting on their own,. Participating companies must commit themselves to subsequently supply antibiotics arising from the program to emerging and developing countries on special terms, because the needs of such countries have priority in the new organization as they already did with DNDi. The German Federal Government has participated in the development of the organization and also contributes to its funding.

In 2016, with CARB-X (Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator) a further Public-Private Partnership was founded. Its participants are the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the Wellcome Trust of London, the AMR Centre of Alderley Park (Cheshire, United Kingdom), the Boston University School of Law and since May 2018 also the British government and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. CARB-X aims to foster worldwide projects for the development of new antibiotics and other antibacterial drugs as well as vaccines and diagnostics for the avoidance or identification of bacterial infections; more precisely the early phases of such projects from drug discovery to testing with healthy volunteers in Phase I. Initially, CARB-X is concentrating on gram-negative bacteria.

An overview of the international programs for promotion and coordination of the development of new antibiotics is provided in the WHO dossier "Targeting innovation in antibiotic drug discovery and development" from 2016.

International Strategies Against Resistance to Antibiotics

Not only the challenge of antibiotics research, but also other aspects of the resistance problem cannot be solved at the national level alone. In view of this, in May 2015 a Global Action Plan was agreed by the plenum of the World Health Organization (WHO) after a powerful speech by Federal Chancellor Angela Merkel at the opening ceremony. In June 2015, the resistance problem was on the agenda of the G7 summit meeting in Elmau, held under German presidency, and at the follow-up meeting of G7 health ministers in October the so-called Berlin Declaration was published. In this, a series of measures to combat antibiotics resistance were agreed by the G7 states, ranging from the strengthening of prevention and promoting the correct use of antibiotics to the examination of global Product Development Partnerships. Among other things, the formulation of these measures took into account the study by The Boston Consulting Group, „Breaking Through the Wall - Enhancing Research and Development of Antibiotics in Science and Industry“ commissioned by the Federal Ministry of Health, as well as the results of a German working group from the pharmaceutical industry, scientists, official bodies and ministries in the framework of the Pharma-Dialog.

The above-mentioned contribution of the Federal Government to the development of GARDP (see above) alongside other activities is one consequence of its commitments in the Berlin Declaration. Another is implemented in the framework of its German Antibiotics Resistance Strategy (DART 2020) which has existed since 2008 and was last updated in 2015 (with an interim report in May 2017).

At the World Economic Forum in Davos in 2016, the pharmaceutical, biotechnology and diagnostics industry together with politicians also committed itself to greater efforts against the resistance problem. More than 80 companies as well as numerous industry associations have signed the "Declaration by the Pharmaceutical, Biotechnology and Diagnostics Industries on Combating Antimicrobial Resistance" - among them the vfa.

The Declaration calls for efforts towards the responsible use of existing antibiotics and the deployment of more pathogen diagnostics, so that the best-suited substance can be directly selected in every case. Both of these work to counteract the emergence of further resistances. The signatories appeal to governments to work with them on new structures for a more reliable and sustainable antibiotics market. This must provide for appropriate economic incentives to companies, and at the same time also encourage the responsible use of antibiotics; for example by ensuring that incomes from antibiotics do not depend exclusively on the volume of prescriptions.

The companies wish to invest even more in research and development for new diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines against infectious diseases. For this, they support new research alliances of companies, public-sector research institutes and other public institutions. In the framework of the WHO Global Action Plan, access to existing and future antibiotics is to be made possible for all those who need them, throughout the world.

The Declaration was supplemented by certain companies with an "Industry Roadmap to Combat Antimicrobial Resistance", in which the approach is set out more precisely. Alongside antibiotics research, it also deals with access to and the appropriate use of antibiotics as well as an examination of existing antibiotics production with reference to environmental aspects.

In 2017, these activities resulted in the formation of the AMR Industry Alliance which coordinates and monitors activities by the industry targeted to the problem of resistance by pathogens. Its first Progress Report appeared in January 2018.

In February 2017, The Boston Consulting Group proposed the foundation of a Global Union for Antibiotics Research and Development (GUARD) . This recommendation, together with analyses and further proposals, is found in the report "Breaking Through the Wall – A Call for Concerted Action on Antibiotics Research and Development" which, like the previous "Breaking Through the Wall" report, was commissioned by the Federal Government.

Also in February 2017, WHO published a list of bacteria for which, in its opinion, new antibiotics are particularly urgently needed, the "WHO priority pathogens list for R&D of new antibiotics".The list is intended to focus the direction of antibiotics research towards special priority goals, in the framework of GARDP as well as with other antibiotics projects. WHO also hopes that governments will adjust their programs for the fostering of fundamental research and applied R&D in the antibiotics field in line with these priorities. All twelve pathogens listed here are (multi-)resistant bacteria, against which hitherto very few new antibiotics have been in development, above all Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas and Enterobacteriaceae. The fact that multi-resistant TB bacteria were not included among the prioritized pathogens led other institutions to emphasize the urgency of further new drugs against these pathogens; among others the final declaration of the G20 meeting of health ministers in May 2017 drew attention to this.

In June 2017, with its updated "Action Plan against Antimicrobial Resistance", the EU affirmed the importance of incentive systems for the development of new antibiotics, but still did not specify which ones should come into use. At the end of June 2017, in its publication "Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance Ensuring Sustainable R&D", the OECD recommended a threefold approach to boosting R&D on resistances and antibiotics: 1. Fostering of fundamental research in academic institutions as well as small and medium-sized companies, which then flows into a "G20 global collaboration platform" as knowledge hub. 2. Support for promising development projects against the pathogens prioritized by WHO. 3. Searching for suitable funding possibilities to make the development of antibiotics more economically attractive and decouple investment in R&D from the need for refinancing through sales of the products.

In the final Leaders' Declaration at their summit meeting in Hamburg on 7-8 July 2017, the G20 heads of government picked up the idea of an R&D collaboration hub. Its purpose is not only to foster fundamental research but also help to coordinate development projects. They also announced their intention to examine further “practical market incentive options”. For them, the priority for R&D is not only the pathogens prioritized by WHO, but also tuberculosis.

In the following months, the Federal Government has led the way in driving forward the development of the Global AMR R&D Hub, as it is now called. On 22 May 2018, the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) was able to announce at the World Health Assembly of WHO that the Hub had started its work. Until further notice, its secretariat has its office in Berlin, organizationally attached to the German Center for Infection Research.

A review of the status of antibiotics research was published in 2017 by the Academy of Sciences and Humanities in Hamburg and the Academy of Sciences Leopoldina: "Antibiotika-Forschung - fünf Jahre danach" (in German; title in English: Antibiotics research - five years on). The title refers to a memorandum by the same publishers in 2012.

Proposals for Funding Measures by the Innovative Medicines Initiative

In January 2018, in the framework of the European Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI) (see above), a consortium of partners from the public sector and companies presented proposals for how expanded development efforts for antibiotics against problem bacteria could be most effectively funded. For this, within the project "Driving re-investment in R&D and responsible antibiotic use" (DRIVE AB) - a component of ND4BB - the consortium had examined numerous suggestions for funding measures that had already been in discussion for some years. In its final report, the consortium determined that it is necessary to have not just one but multiple funding instruments in parallel, and that these should include both the direct funding of project stages and also the prospect of rewards for successful development. The following measures are seen as especially promising and effective:

- (Non-repayable) grants for research institutions and companies.

- Pipeline Coordination: State or non-profit organizations should monitor the antibiotics pipeline and actively support selected R&D projects.

- Market Entry Rewards: One-off payments to companies that have brought an antibiotic against a problem pathogen to approval, linked with obligations to make the substance accessible to needy countries and to promote its rational use. On conferment of the Reward, prior subsidies for clinical development must be repaid.

- Long-Term Supply Continuity Model: Payments to manufacturers, delinked from sales turnover, to guarantee a reliable production volume of important patent-free antibiotics.

The coordination of all funding measures is to be carried out by the G20 Global R&D Collaboration Hub.

Grants and Pipeline Coordination already exist but should be further expanded. Here, "standard sustainable use and equitable availability principles" should be applied, observance of which should be monitored an ongoing basis by methods that are still to be developed.

Market Entry Rewards by contrast would be a completely new funding instrument. According to the consortium, Market Entry Rewards of 1 billion US dollars respectively (in addition to achieved turnover) could quadruple the number of antibiotics in the next 30 years. The value of the Reward has been adjusted with simulations, and roughly corresponds to earlier proposals by The Boston Consulting Group and the British group Review on Antimicrobial Resistance. The Rewards would be implemented at international level by the G20, with the EU bearing at least one-third of the costs. This could be tested initially in a pilot phase by certain EU states that decide to participate. The payment could be made through the European Investment Bank following EU approval of the relevant antibiotic.

To ensure Long-Term Supply Continuity, interested countries and institutions should test a joint procurement process for a patent-free antibiotic with fragile provision (e.g. benzylpenicillin) in which, in contrast to existing practice, its manufacturer would be paid independently of its actual sales ("delinked").

Further information material:

- Handlungsempfehlungen zur Minderung von Antibiotika-Resistenzen (in German; title in English: Recommendations for action to reduce antibiotics resistance)

(1) Approved in the USA since August 2017 against urinary tract infections.

(2) Approved in the USA since June 2017 against skin infections.

(3) Submitted for approval in the USA in October 2017 against certain urinary tract infections and blood infections.

(4) Approved in the USA since October 2018 for the treatment of respiratory tract and skin infections.

(5) In approval procedure in the USA since August 2018 for the treatment of skin infections.

(6) Was already in approval procedure in the EU between June 2016 and March 2017, but the application was withdrawn; a new application with additional data is planned.

(7) Supported by CARB-X

(8) Developed by the TB Alliance without company participation.

(9) Approved in the USA since March 2015.

(10) Approved in the USA since March 2016.

(11) Submitted for approval in the USA in October 2017.

(12) Announced by the development partners Entasis Therapeutics and GARDP in July 2017.

(13) Only biopharmaceutical against bacteria.

(14) No own research for antibiotic active ingredients; develops new forms of administration for licensed-in, acquired or patent-free active ingredients.